BALZAC'S WORKING LIFE: Good Coffee Worth The Trouble

Prof. Articolo RoutchkoLet us take a day in Balzac's working life, a day typical of thousands.

Eight o'clock in the evening. The citizens of Paris have long since finished their day's work and left their offices, shops or factories. After having dined with their families, or their friends, or alone, they were beginning to pour out into the streets in search of pleasure. Some strolled along the boulevards or sat in café's, others were still putting the finishing touches to their toilet before the mirror prior to a visit to the theater or a salon. Balzac alone was asleep in his darkened room, dead to the world after sixteen or seventeen hours spent at his desk.

Nine o'clock. In the theaters the curtain had already gone up, the ballrooms were crowded with whirling couples, the gambling-houses echoed to the chink of gold, in the side streets furtive lovers pressed deeper into the shadows - but Balzac slept on.

Ten o'clock. Here and there lights were being extinguished in houses, the older generation was thinking of bed, fewer carriages could be heard rolling over the cobbles, the voices of the city grew softer - and Balzac slept.

Eleven o'clock. The final curtain was falling in theaters, the last guests were turning homeward from the parties or salons, the restaurants were dimming their lights, the last pedestrians were disappearing from the streets, the boulevards were emptying as a final wave of noisy revelers disappeared into the side streets and trickled away - and Balzac slept on.

Midnight. Paris was silent. Millions of eyes had closed. Most of the lights had gone out. Now that the others were resting it was time for Balzac to work. Now that the others were dreaming it was time for Balzac to wake. Now that the day was ended for the rest of Paris his day was about to begin. No one could come to disturb him, no visitors to bother him, no letters to cause him disquiet. No creditors could knock at his door and no printers send their messengers to insist on a further installment of manuscript or corrected proofs. A vast stretch of time, eight to ten hours of perfect solitude, lay before him in which to work at his vast undertaking. Just as the furnace which fuses the cold, brittle ore into infrangible steel must not be allowed to cool down, so he knew that the tensity of his vision must not be allowed to slacken: "My thoughts must drip from my brow like water from a fountain. The process is entirely unconscious."

He recognized only the law which his work decreed: "It is impossible for me to work when I have to break off and go out. I never work merely for one or two hours at a stretch." It was only at night, when time was boundless and undivided, that continuity was possible, and in order to obtain this continuity of work he reversed the normal division of time and turned his night into day.

Awakened by his servant knocking gently on the door, Balzac rose and donned his robe. This was the garment which he had found by years of experience to be the most convenient for his work. In winter it was of warm cashmere, in summer of thin linen, long and white, permitting complete freedom of movement, open at the neck, providing adequate warmth without being oppressive, and perhaps a further reason why he chose it was because its resemblance to a monk's robe unconsciously reminded him that he was in service to a higher law and bound, so long as he wore it, to abjure the outside world and its temptations. A woven cord (later replaced by a golden chain) was tied loosely round this monkish garment, and in place of the crucifix and scapular there dangled a paper-knife and a pair of scissors. After taking a few steps up and down the room to shake the last vestiges of sleep from his mind and send the blood circulating more swiftly through his veins, Balzac was ready.

The servant had kindled the six candles in the silver candelabra on the table and drawn the curtains tightly as if this were a visible symbol that the outer world was now completely shut off, for Balzac did not want to measure his hours of work by the sun or the stars. He did not care to see the dawn or to know that Paris was waking to a new day. The material objects around him faded into the shadows - the books ranged along the walls, the walls themselves, the doors and windows and all that lay beyond them. Only the creatures of his own mind were to speak and act and live. He was creating a world of his own, a world that was to endure.

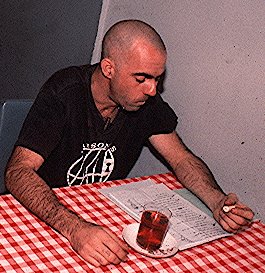

Balzac sat down at the table where, as he said, "I cast my life into the crucible as the alchemist casts his gold." It was a small, unpretentious, rectangular table which he loved more than the most valuable of his possessions. It meant more to him than his stick that was studded with turquoises, more than the silver plate that be had purchased piece by piece, more than his sumptuously bound books, more than the celebrity he had already won, for he had carried it with him from one lodging to another, salvaged it from bankruptcies and catastrophes, rescued it like a soldier dragging a helpless comrade from the turmoil of battle. It was the sole confidant of his keenest pleasure and his bitterest grief, the sole silent witness of his real life: It has seen all my wretchedness, knows all my plans, has overheard my thoughts. My arm almost committed violent assault upon it as my pen raced along the sheets. No human being knew so much about him, and with no woman did he share so many nights of ardent companionship. It was at this table that Balzac lived - and worked himself to death.

A last look round to make sure that everything was in place. Like every truly fanatical worker, Balzac was pedantic in his method of work. He loved his tools as a soldier loves his weapons, and before he flung himself into the fray he had to know that they were ready to his hand. To his left lay the neat piles of blank paper. The paper had been carefully chosen and the sheets were of a special size and shape, of a slightly bluish tinge so as not to dazzle or tire the eyes and with a particularly smooth surface over which his quill could skim without resistance. His pens had been prepared with equal care. He would use no other than ravens' quills. Next to the inkwell - not the expensive one of malachite that had been a gift from some admirers, but the simple one that had accompanied him in his student days - stood a bottle or two of ink in reserve. He would have no precaution neglected that would serve to insure the smooth, uninterrupted flow of his work. To his right lay a small notebook in which he now and then entered some thought or idea that might come in useful for a later chapter. There was no other equipment. Books, papers, research material were all unnecessary. Balzac had digested everything in his mind before be began to write.

He leaned back in his chair and rolled back the sleeve of his robe to allow free play to his right hand. Then he spurred himself on with half-jesting remarks addressed to himself, like a coachman encouraging his horses to pull on the shafts. Or be might have been compared to a swimmer stretching his arms and easing his joints before taking the steep plunge from the diving-board.

Balzac wrote and wrote, without pause and without hesitation. Once the flame of his imagination was kindled it continued to glow. It was like a forest fire, the blaze leaping from tree to tree and growing hotter and more voracious in the process. Swiftly as his pen sped over the paper, the words could hardly keep pace with his thoughts. The more he wrote the more he abbreviated the words so as not to have to think more slowly. He could not allow any interruption of his inner vision, and he did not raise his pen from the paper until either an attack of cramp compelled his fingers to loosen their hold or the writing swam before his eyes and he was dizzy with fatigue.

The streets were silent and the only sound in the room was the soft swish of the quill as it passed smoothly over the surface of the paper or from time to time the rustle of a sheet as it was added to the written pile. Outside the day was beginning to dawn, but Balzac did not see it. His day was the small circle of light cast by the candles, and he was aware of neither space nor time, but only of the world that he himself was fashioning.

Now and then the machine threatened to run down. Even the most immeasurable will-power cannot prolong indefinitely the natural measure of a man's physical strength. After five or six hours of continuous writing Balzac felt he must call a temporary halt. His fingers had grown numb, his eyes were beginning to water, his back hurt, his temples throbbed, and his nerves could no longer bear the strain. Another man would have been content with what he had already done and would have stopped work for the night, but Balzac refused to yield. The horse must run the allotted course even if it foundered under the spur. If the sluggish carcass declined to keep up the pace recourse must be had to the whip. Balzac rose from his chair and went over to the table on which stood the coffee pot.

Coffee was the black oil that started the engine running again; for Balzac it was more important than eating or sleeping. He hated tobacco, which could not stimulate him to the pitch necessary for the intensity with which he worked. Tobacco is injurious to the body, attacks the mind, and makes whole nations dull-witted, but he sang a paean in praise of coffee:

Coffee glides down into one's stomach and sets everything in motion. One's ideas advance in column of route like battalions of the Grande Armée. Memories come up at the double bearing the standards which are to lead the troops into battle. The light cavalry deploys at the gallop. The artillery of logic thunders along with its supply wagons and shells. Brilliant notions join in the combat as sharpshooters. The characters don their costumes, the paper is covered with ink, the battle has begun and ends with an outpouring of black fluid like a real battlefield enveloped in swathes of black smoke from the expended gunpowder.

Without coffee he could not work, or at least he could not have worked the way he did. In addition to paper and pens he took with him everywhere as an indispensable article of equipment the coffee-machine, which was no less important to him than his table or his white robe. He rarely allowed anybody else to prepare his coffee since nobody else would have prepared the stimulating poison in such strength and blackness. And just as in a sort of superstitious fetishism be would use only a particular kind of paper and a certain type of pen, so he mixed his coffee according to a special recipe, which has been recorded by one of his friends: This coffee was composed of three different Varieties of bean: Bourbon, Martinique, and Mocha. He bought the Bourbon in the rue de Montblanc, the Martinique in the rue des Vieilles Audriettes, and the Mocha in the Faubourg St. Germain from a dealer in the rue de l'Université whose name I have forgotten though I repeatedly accompanied Balzac on his shopping expeditions. Each time it involved half a day's journey right across Paris, but to Balzac good coffee was worth the trouble.

Coffee was his hashish, and since like every drug it had to be taken in continually stronger doses if it was to maintain its effect, he had to swallow more and more of the murderous elixir to keep pace with the increasing strain on his nerves. Of one of his books he said that it had been finished only with the help of streams of coffee. In 1845, after nearly twenty years of overindulgence, he admitted that his whole organism had been poisoned by incessant recourse to the stimulant and complained that it was growing less and less effective, and that it caused him dreadful pains in the stomach. If his fifty thousand cups of strong coffee (which is the number he is estimated to have drunk by a certain statistician) accelerated the writing of the vast cycle of the Comédie humaine, they were also responsible for the premature failure of a heart that was originally as sound as a bell. Dr. Nacquart, his lifelong friend and physician, certified as the real cause of his death an old heart trouble, aggravated by working at night and the use, or rather abuse, of coffee, to which he had to have recourse in order to combat the normal human need for sleep.

The clock struck eight at last and there came a tap at the door. His servant, Auguste, entered with a modest breakfast on a tray. Balzac rose from the table where he had been writing since midnight. The time had come for a brief rest. Auguste drew back the curtains, and Balzac stepped to the window to glance at the city which he had set out to conquer. He again became conscious that there was another world and another Paris, a Paris that was beginning its work now that his own labors had for the time being come to an end. Shops were opening, children were hastening to school, carriages were rolling along the streets, in offices and counting-houses men were sitting down at their desks.

To relax his exhausted body and refresh himself for the further tasks that awaited him, Balzac took a hot bath. He usually spent an hour in the tub, as Napoleon had liked to do, for it was the only place where he could meditate without being disturbed, meditate without having immediately to write down the substance of his thoughts, surrender himself to the voluptuous pleasure of creative dreaming without the necessity for simultaneous physical effort. Hardly had he resumed his robe, however, when steps could be heard outside the door. Messengers were arriving from his various printers, like Napoleon's dispatch-riders sent during the battle to maintain contact between the command post and the battalions that were carrying out his orders. The first arrival demanded a fresh installment of the current novel, the still damp manuscript of the night that had just passed. Everything that Balzac wrote had to be set up in print at once, not only because the newspaper or publisher was waiting for it as for the payment of a debt that was due - every novel had been sold before it was written - but because Balzac in the trance-like state in which he worked did not know what he was writing or what he had already written. Even his keen eye could not survey the dense jungle of his manuscripts. Only when they were in print and he could review them paragraph by paragraph, like companies of soldiers marching past at an inspection, was the general in Balzac able to discern whether he had won the battle or whether he had to renew the assault.

Other messengers from the printers, the newspapers, or the publishers brought proofs of the pages he had written two nights before and sent to press on the previous day, together with the second or third proofs of earlier installments. Whole piles of fresh galleys, often five or six dozen of them still damp from the proof-press, overflowed his little table and claimed his attention.

At nine o'clock his brief respite was at an end. His form of rest, as he once said, consisted of a change of task. But correcting proofs was not an easy business so far as Balzac was cancerned. It involved not merely the elimination of printers' errors and slight emendations of style or content, but the complete rewriting and recasting of the original manuscript. In fact he regarded the first printed proofs as a preliminary draft, and to no task did be devote more passionate energy than to the gradual shaping of his plastic prose in a sequence of proof-sheets which he scrutinized and altered time after time with a keen sense of artistic responsibility. In everything that concerned his work he was tyrannical and pedantic, and he insisted on the galleys being printed according to rules that he himself laid down. The sheets had to be specially long and wide, so that the printed text looked like the pip on an ace in a pack of playing cards. The margins to right and left, above and below, were vast blank spaces for corrections and alterations. Moreover, he would not accept proofs printed on the usual cheap yellowish paper, but demanded a white background against which every letter could stand out clearly.

Balzac sat down again at his little table. The first swift glance - he possessed the gift of his Louis Lambert of being able to read six or seven lines at once - was followed by a wrathful stab of the pen. He was dissatisfied. Everything he had written on the previous day, and the day before that, was bad. The meaning was obscure, the syntax confused, the style defective, the sequence clumsy. It must all be changed and made dearer, simpler, less unwieldy. The frenzy with which he attacked the square of printed text, like a cavalryman charging at a solid phalanx of the enemy, can be seen from the savage jabs and strokes from his spluttering pen that stretch right across the sheet. A saber thrust with his quill and a sentence was torn from its context and flung to the right, a single word was speared and hurled to the left, whole paragraphs were wrenched out and others plugged in. The normal symbols used as directions to the compositor no longer sufficed, and Balzac had to employ symbols of his own invention. Before long there was not enough room in the margins for further corrections, which now contained more matter than the printed text. The marginal corrections themselves were scored with symbols drawing the compositor's attention to supplementary afterthoughts, until what had once been a desert of white space with an oasis of text in the middle was covered with a spider's web of intersecting lines, and he had to turn the sheet over to continue his corrections on the back. Yet even that was not enough. When there was no more space for the symbols and criss-cross lines by which the unhappy compositor was to find his way about, Balzac had recourse to his scissors. Unwanted passages were removed bodily and fresh paper pasted over the gap. The beginning of a section would be stuck in the middle and a new beginning written, the whole text was dug up and raked over and this chaotic mass of printed text, interpolated corrections and alterations, symbols, lines, and blots went back to the printer in an incomparably more illegible and unintelligible state than the original manuscript.

In the newspaper and printing offices laughing throngs gathered round to examine the astonishing scrawl. The most experienced compositors declared their inability to decipher it and though they were offered double wages they refused to set up more than une heure de Balzac a day. It took months before a man learned the science of unraveling his hieroglyphics, and even then a special proofreader had to revise the compositor's often very hypothetical surmises.

Their task, however, was still only in its initial stages. When Balzac received the second set of galleys, he flung himself upon them with the same rage as before. Once more he would tear apart the whole laboriously constructed edifice, bestrewing each sheet from top to bottom with further emendations and blots, until it was no less involved and illegible than its predecessor. And this would happen six or seven times, except that in the later proofs he no longer broke up whole paragraphs but merely altered individual sentences and ultimately confined himself to the substitution of single words. In the case of some of his books Balzac recorrected the proof-sheets as many as fifteen or sixteen times, and this alone gives us a faint idea of his extraordinary productivity. In twenty years he not only wrote his seventy-four novels, his short stories, and his sketches, but he rewrote them again and again before they finally appeared in print.

Neither financial need nor the entreaties of his publishers, who alternated between friendly reproaches and legal action, could dissuade Balzac from pursuing his expensive system. On numerous occasions he forfeited half his fee, and sometimes the whole of it, because he had to pay the cost of corrections and resetting out of his own pocket. But it was a matter of artistic integrity, and on this point he remained inexorable. The editor of a newspaper once printed an installment of one of his novels without waiting for the final proof or obtaining Balzac's imprimatur, with the result that Balzac broke off relations with him for ever. To the outside world be appealed frivolous, slipshod, and covetous, but as an artist be waged the most conscientious and unyielding struggle of any writer in modern literature. Because he alone knew of the energy and self-sacrifice that went to the perfection of his work in his secluded laboratory, where his painstaking absorption was invisible to those who saw only the finished product, he treasured his proof-sheets as the sole faithful and reliable witnesses. They were his pride, the pride not so much of the artist as of the worker, the indefatigable craftsman. He therefore compiled one copy of each of his books, made up of the successive layers of revised proofs in their various stages together with the original manuscript, and had it bound in a massive volume that sometimes comprised about two thousand pages as compared with the two hundred or so of the published novel. In some cases the manuscript was merely attached instead of being bound in with the proofs. As Napoleon distributed princely or ducal titles and coats-of-arms to his Field Marshals and other loyal adherents, Balzac presented these volumes from the vast realm of the Comédie humaine to his friends as the most precious gift he had to bestow:

I offer these volumes only to those who love me. They are witnesses to my lengthy labors and to that patience of which I have spoken to you. It was these dreadful pages on which I spent my nights.

Most of them were given to Madame de Hanska, but Madame de Castries, the Countess Guidoboni-Visconti, and his sister were also among the recipients. That the few people singled out for such an honor were fully conscious of the value of these unique documents may be judged from the reply of Dr. Nacquart when he received as a reward for his years of friendship and medical care the volume containing the proof-sheets of Le lys dans la vallée:

This is a truly remarkable monument, and it should be made accessible to all who believe in the perfection of beauty in art. How instructive too it would be for the public, which believes that the productions of the mind are conceived and created with as little effort as they can be read! I wish my library could be set up in the middle of the Place Vendôme, so that those who appreciate your genius might learn to estimate at their true value the conscientiousness and tenacity with which you work.

With the exception of Beethoven's notebooks there are hardly any documents existing today in which the artist's struggle for expression is more tangibly demonstrated than in these volumes. The elemental force with which Balzac was endowed, the titanic energy that went to the making of his books, can here be studied more vividly than in any portrait or contemporary anecdote. Only by knowing them can we know the real Balzac.

The three or four hours during which he worked at his proofs, which he jokingly called faire sa cuisine littéraire, took up the whole forenoon. Then he pushed aside the pile of papers and refreshed himself with a light lunch, consisting of an egg, a sandwich or two, or a little pasty. He was fond of good living and the heavy, greasy dishes of his native Touraine, the tasty rillettes, the crisp capons and the juicy red meat, while he knew the red and white wines of his hone province as a pianist knows his keyboard; but while he was working be denied himself every luxury. He was aware that eating makes a man sluggish, and he had no time to be sluggish. There was no time even for an interlude of rest, and he very soon moved his armchair up to the little table again either to continue correcting proofs, jot down memoranda, work at an article or two, or write letters. At last, toward five o'clock, he laid aside his pen for the day. He had seen nobody and had not even cast a glance at a newspaper, but now he could ease off a little. Auguste served supper, and he would sometimes receive a visit from a publisher or a friend, but generally he remained alone with his thoughts, which perhaps revolved around the work he was to do during the coming night. He never, or hardly ever, went out into the street, for he was too fatigued. At eight o'clock, when others were going out to seek their pleasures, he went to bed and fell asleep at once. His sleep was deep and dreamless. Like everything else he did, it was characterized by extreme intensity. He slept to forget that all the work he had already done would not relieve him of the work which was to be done on the morrow, and the morrow after that, until the last hour of his life. At midnight his servant entered, lit the candles, and therewith kindled once more the flame of work in the awakened Balzac.